Written by Vanessa Toh - Physiotherapist - Brisbane

Are you able to:

- perform proper diaphragmatic breathing?

- contract and lengthen/relax your pelvic floor?

- maintain effective intra-abdominal pressure throughout your abdomen?

- Sustain core control from the start of the squat, throughout descent and ascent?

If you can’t answer yes to every one of these questions then you really need to better understand how

your core works when you lift!

Because...

When it comes to lifting anything of substance (like in a squat)

Having the ability to control our position and movement is essential! Especially if you’re keen to spend

more time in the gym and less on a treatment table.

This control is determined by our level of ‘core stability’. Or to be more specific, our ability to maintain

intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), tension and positioning throughout the entire movement.

The 2 Misunderstood Concepts of Core Stability

Before you load up any bar there are 2 separate but intricately linked concepts you really need to understand about “core stability”:

1. Core control basics

Where your intrinsic and extrinsic core muscles (diagram below) synchronise concentrically and eccentrically to transfer pressure from one part to another.

This is what enables you to maintain your rib cage and pelvic stacked positioning throughout the squat. It’s what some people will call the ‘canister position’.

This stacked position provides us an optimal position to sustain and maximise intra-abdominal pressure, which is the necessary foundation for the 2nd concept.

2. Bracing Essentials

Where core control is to position…

Bracing is to build and sustain pressure!

It’s your ability to maximize and sustain intra-abdominal pressure throughout the squat (or any movement really). It happens via coordination of all our intrinsic and extrinsic core muscles to maintain a better “canister” position.

If you look at the skeleton you’ll see the difference between a strong ‘canister’ and a ‘scissor’ position.

So why is this actually important?

It allows:

minimal energy leakage

the glutes, hip flexors fire more efficiently and

the lumbar erectors and thoracolumbar fascia to transfer force to move the bar

Reflecting this clinically,

I often see lifters present with hip or low back tightness who have difficulty with coordinating and building sufficient intra-abdominal pressure. If this is you, we know what to do!!

Hopefully you’re following along nicely:

Use core control to get into your canister position and brace to increase intra-abdominal pressure and maintain stability and force transfer.

Relatively straightforward,

But…

How does intra-abdominal pressure produce pelvic and spinal stability?

Let’s start with a very simple overview:

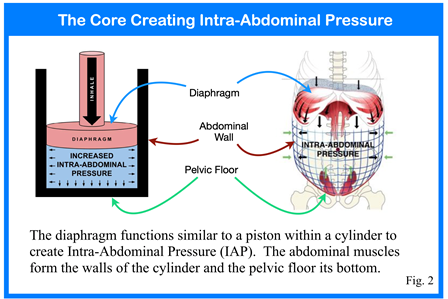

Diaphragm creates downward pressure

Pelvic floor create upward pressure

Abdominal wall holds tight

It often helps to think of the core creating intra-Abdominal pressure like a piston as per the below diagram.

Now this is where it starts to get a little more technical!

If you’re interested in the detail read on, however if you’d rather someone just tell you where you’re at and what you need to do the quickest way is to simply book in and see your trusted practitioner.

The Role of the Diaphragm

As depicted in the diagram above, the diaphragm has origin attachments to the lumbar spine. Therefore, the diagram has both respiratory and stabilization functions. Proper diagram breathing leads to optimal intra-abdominal pressure. This imposes a stabilization effect on the spine during compound lifts like the squat.

The Role of the Pelvic Floor

Your pelvic floor muscles function to prevent your abdominal and pelvic organs from bottoming out, as well as helping you to breathe, cough, copulate, urinate, defecate and giving birth. It has an incredibly important job of being able to manage the pressure being placed upon it. In the context of the squat, we are going to look at the pelvic floor’s relationship with the other core musculature to generate and sustain intra-abdominal pressure.

When we inhale, our ribs expand and diaphragm contracts to flatten, lower and move our organs down. The abdominal wall and pelvic floor stretch to a certain point in an eccentric contraction and then hold with an isometric contraction. During this, our pelvic floor muscles then lengthen and expand to make room for your organs (indicated by blue arrows above). Whereas when we exhale, our diaphragm lifts and our pelvic floor and abdominal wall contract and shorten, returning to their resting position.

In order to maximise intra-abdominal pressure during the squat, the entire (front and back) pelvic floor needs to contract and raise up, which allows a stronger pressurised cylinder. To do this we need to be able to contract our pelvic floor in conjunction with our breathing and bracing.

Linking it all together through your Thoraco Lumbar Fasica

One of the keys to connecting intra-abdominal pressure to core stability is the Thoraco-lumbar fascia. A dense layer of connective tissue serving as a junction point for the attachment of numerous extrinsic core muscles:

gluteus maximus

latissimus dorsi

quadratus lumborum

spinal erectors and

external oblique and intrinsic core muscles

transversus abdominis

internal oblique

When proper building of intra-abdominal pressure and bracing occurs, this exerts an outwards force against the spine and abdominal wall leading to an eccentric contraction of the entire abdominal wall including front and back (blue arrows).

This in turn loads the thoraco-lumbar fascia!

Now there’s a huge difference between understanding what needs to happen and actually doing it. And to be perfectly honest, it’s nearly impossible to self assess where your core control and bracing is at without a separate pair of eyes. If it’s purely technical, a good coach should be able to pick it up and cue you into position.

A proper assessment will however look at breathing control, manual muscle testing and fascial restrictions. All things a trusted healthcare practitioner who’s got some experience in lifting can help you with.

If you’re not 100% sure if you’ve got it right and want someone to look over your ability to control your core, brace and perform both a safe and efficient movement then book an appointment online.